Indonesia Survives Food- & Energy Crisis

Part I

Problems Emerging countries

mdeboer FD / eyesonindonesia

Amsterdam, June 11th 2022– A severe energy crunch plus an equally serious global food shock hit countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America hard. Inflation and a stagnant economy make them very vulnerable. Their debts have risen quickly during the corona period and with rising interest rates they are getting into trouble.

Emerging economies such as Indonesia are being hit hard by higher energy and food prices.

They are extra vulnerable because the debt burden has increased very sharply during the corona period, while interest rates are now also rising.

Countries such as Argentina, El Salvador, Pakistan, Ghana, Tunisia and Kenya are in the danger zone, but Egypt, Malaysia and Chile are also at risk.

Take Pakistan for example.

There, government officials no longer have to show up at work on Saturdays for the time being. If the buildings are closed, they do not need to be cooled with air conditioners and the country saves energy, or so the idea. It is one of the solutions that the government in Islamabad has come up with to the increasingly dire energy problem.

But it seems to be senseless fighting.

The country has run out of financial reserves and is now being hit hard by high oil, gas and coal prices. Because the treasury is almost empty, Islamabad has requested support from the International Monetary Fund, but that will only come if the subsidies on fuels are phased out in order to reduce the deficits. The government is wary of this, for fear of social unrest. Meanwhile, foreign banks no longer provide trade credit, which means that hardly any oil can be imported.

In a little while, Pakistan will be the next in the line of defaulters after Lebanon and Sri Lanka.

Fuel shortages and crop failures

Pakistan is no exception.

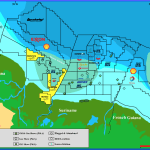

Everywhere in Asia, Africa and Latin America there are fuel shortages and long lines at gas stations: from Laos and Kenya to Argentina.

Airlines will only fly to various countries in South Asia and Africa if they can take enough kerosene with them for the return flight or if they know that they can refuel in a neighboring country.

Emerging and low-income countries dependent on foreign fuels struggle with high prices in international markets, weak currencies and competitive buyers mainly from European countries.

They scour the markets in the Middle East in search of diesel and kerosene to replace Russian products, says

Here too, the international markets offer no solace, because after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, global food prices have risen to levels not seen in at least thirty years.

How farmers are going to maintain their production without affordable diesel for their machines and with a shortage of fertilizer, largely from Russia and Ukraine, is the question in many countries.

Small step to recession

In addition to this global energy crunch,

S&P Global speaks of an equally severe if not worse global food shock, a food crisis that, according to the American agency, will last until 2024 and possibly longer.

In countries such as Turkey, India, Mexico, Egypt and most sub-Saharan countries, people spend 25% to more than 40% of their income on food.

There, the 30% higher food prices have an unusually hard effect on inflation. It is then a small step towards recession, say more and more economists. And from a lack of fiscal space to social unrest is not a big step either.

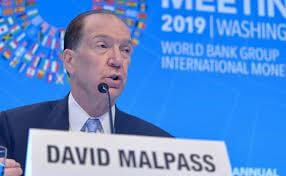

“The risk of high inflation and economic stagnation is significant, with potentially destabilizing effects on low- and middle-income economies,” World Bank President

David Malpass said in the Global Economic Prospects report last week. “If current stagflation pressures intensify, financially vulnerable emerging and low-income countries will struggle.”

Last week it was the OECD, the think tank of the club of rich economies, that again pointed to the debt burden in the emerging countries, which has risen sharply during the corona crisis, both public and private. Higher interest rates to curb inflation and prop up weak currencies make it much more difficult to bear those debts, especially when a large proportion of foreign currency liabilities have to be met.

Negative spiral

Rising interest rates and reversals in capital flows exacerbate vulnerabilities, the OECD said in its semi-annual outlook. “Should capital outflows increase, leading to a further depreciation of currencies, the debt burden of those countries could increase significantly.”

A negative spiral is then quickly the result.

End Part I

See Part II tomorrow

mdeboer FD / eyesonindonesia