The Four Extremely Sad and Very Bad Elephants

And the possible resurrection East-Timor

Part II

Nick Morris / eyesoneast-timor

The people of Timor-Leste have lived on the island for over 40,000 years.

The first elephant, Portugal, saw them as a source of slaves and then colonized, waging war against local kingdoms and killing around 5 percent of the local population. Even as an overseas province, little investment was made in healthcare, education, or infrastructure.

The second elephant, Japan, invaded during World War II, killed 10–15 percent of the population, and used Timorese women as comfort women for its troops.

The third elephant, Indonesia, invaded in 1975 after Portugal abandoned its colony and undertook systematic genocide and displacement of the population, killing up to 30 percent. It was only in 2002 that Timor-Leste achieved independence.

And the fourth elephant, Australia, abandoned Timor-Leste to the Japanese, turned a blind eye to human rights abuses in the 1975–1999 period, and sought to extract oil and gas resources from the infant nation in underhanded ways. The fifth elephant, China, has provided support in the post-independence period.

Introduction

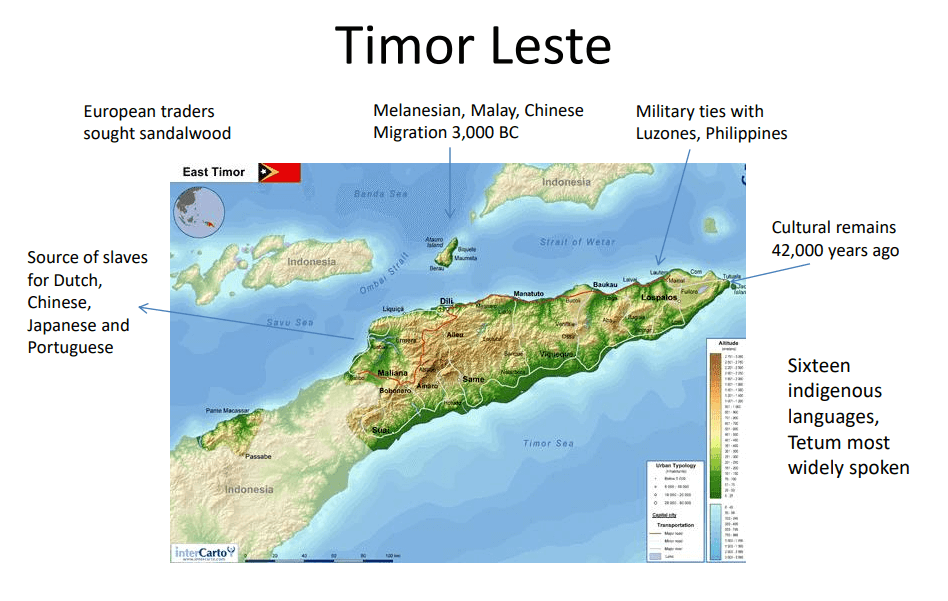

The Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste consists of the eastern part of the island of Timor, plus the nearby islands of Alauro and Jaco, with Dili as its capital city. Cultural remains at Jerimalai, on the eastern tip, have been dated to 42,000 years ago (Marwick et al. 2016). Descendants of Veddo-Australoid people are still believed to live in the mountainous interior. Around 3000 BC, a second migration brought Melanesians, and proto-Malays arrived from south China and north Indochina (Magalhães 1994).

Prior to European colonization, Timor was included in Indonesian, Malaysian, Chinese, and Indian trading networks and had military ties with the Luzones of northern Philippines (Lamoureux 2004; Pigafetta 1969).

The relative abundance of sandalwood attracted European traders from the early sixteenth century, and the Timorese were a source of slaves exported to Europe and other parts of Asia (Hägerdal 2020). Sixteen languages are indigenous to East Timor, of which 12 are closely related to each other. Tetum, an Austronesian language, is the most widely spoken. In the 1850s, Portuguese became a more dominant language, and it remained the official language until 1975. After independence in 2002, Timor-Leste named Portuguese and Tetum its national languages.

This chapter tells the story of how a small country that was among the poorest in the world in the 1970s has been exploited by numerous larger ones.

It identifies four elephants – Portugal, Japan, Indonesia, and Australia – which have in various ways abused the East Timorese population, and a fifth, China, which has provided strong support post-independence. Timor-Leste’s early attempts at independence foundered because of a self-serving lack of support from the international community, leading to one of the worst twentieth-century examples of genocide.

That the country eventually achieved independence only occurred because of a few pieces of “good luck” – a TV crew in the right place at the right time, the Asian financial crisis, the Nobel Peace Prize being awarded to its leaders, and international public opinion saying enough is enough.

Colonial Exploitation by Elephant One: Portugal 7th to early 20th Century

Both the Dutch and Portuguese sought to establish control over parts of Timor, and during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries attempted to establish alliances with various Timorese kingdoms and with the Topasses, who dominated the island at the time (Boxer 1947). The Topasses, or ‘black Portuguese’, combined indigenous and Portuguese blood and culture (Andaya 2010). In 1642, Timorese forces allowed the Portuguese to conquer the kingdom of Waiwiku-Wehale, which had a spiritual authority acknowledged by many other kingdoms, thus enhancing Portugal’s prestige and fostering the spread of Catholicism (Thomaz 2008). In the eighteenth century, some kingdoms rebelled against the Portuguese and the Dutch, leading to the battles of Cailaco in 1727, and Penfui in 1749 (Durand 2011).

The Topasses welcomed the opening of a Catholic seminary by Portuguese Dominicans in Oecusse (Yoder 2016), but subsequently sought to get rid of the Dutch, who eventually scaled back their interference in internal Timorese affairs.

The colony of Portuguese Timor was founded in 1769, with the population who were loyal to the Portuguese (1,200 people) migrating from Oecusse to Dili (Sousa 2001). Subsequent administration of East Timor involved division into 11 military districts, encroaching on local powers. Taxes were increased, forced labor was introduced, and the Timorese were ordered to plant coffee and give 20 percent of their crop to the Portuguese (Roque 2010; Schwarz 1994).

This led in due course to various revolts, and eventually to the assassination of Governor Alfredo de Lacera e Maia in 1887. A subsequent governor, Celestino da Silva, conducted more than 20 military campaigns between 1894 and 1908 against the local kingdoms and was the first to use machine guns, grenades, and naval gunboats against Indigenous warriors who only had bows and arrows, spears, and the occasional hunting rifle (Roque 2015).

Nevertheless, many of these campaigns, especially that against the Manufahi, ended without clear victory. By 1911, relations had deteriorated sufficiently that the Manufahi joined forces with other kingdoms against the Portuguese, which led to the Great War of 1911–1912 in which 15,000–25,000 Timorese died, more than 5 percent of the total population (Durand 2011).

Invasion by Elephant Two: Japan (1941–1945)

On December 17, 1941, despite Portugal’s neutrality in World War II, 1,100 Australian and Dutch soldiers invaded East Timor, seeking to prevent it from being used as a base for an invasion of Australia (Australian Department of Defence 2002). This then prompted the Japanese to bomb Dili on February 8, 1942 and to invade the city with up to 20,000 troops on February 20 (Borda d’Água 2007). The Allied soldiers retreated to the mountains, assisted by the local population. When the Australians, who lost only 40 men, were evacuated, the Japanese reprisals against those who had helped them were severe, with between 45,000 and 70,000 deaths, some 10–15 percent of the pre-war population (Dunn 1983). Japanese treatment of the East Timorese population was barbaric, with many of the women forced or co-erced into sexual slavery as “comfort women” for their troops (Tanaka 2002).

East Timor was returned to Portuguese control following the Japanese surrender, in return for Portugal allowing the Allies to use air bases in the Atlantic Azores islands (Roberts 2019).

Continued Neglect by Portugal (1946–1974)

Portugal continued to neglect the colony, which was declared an overseas province in 1955, and very little investment was made in healthcare, education, or infrastructure (Dunn 1983). Very few Timorese were educated: they lived in the poorer sections of towns and worked as manual laborers.

As late as 1971, the East Timorese were among the world’s poorest people, earning US$1.48 per week (while Indonesians in the nearby Sunda Islands were earning US$5).

Around 95 percent of businesses in East Timor were controlled by Chinese, and the Europeans living there were mostly administrators, political exiles, military personnel, and merchants. The airport in Dili could not accommodate large planes until 1960, and such roads as existed were poorly built. Although oil and gas were present offshore, the Portuguese, Australian, and American companies that expressed interest never invested enough to exploit them commercially (Lamoureux 2004).

Genocide by Elephant Three: Indonesia (1975–1999)

Following the 1974 Portuguese Carnation Revolution, Portugal abandoned its colony, and Indonesia launched a series of military offensives starting in September 1975.

The Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor, known as Fretilin, declared the territory’s independence on November 28, 1975 and requested that the United Nations send a peacekeeping force. However, only a handful of countries – China, Cuba, Vietnam, and previous Portuguese colonies – recognized the new entity, and no Western power supported Fretilin.

Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam made it clear to the Indonesians that Australia would prefer that East Timor be incorporated into Indonesia than to remain independent, fearing it might become a base for Chinese or Soviet influence in the region (Roberts 2019).

Other rival East Timorese political parties – notably the Timorese Democratic Union (UDT), and the Timorese Popular Democratic Association (APODETI) – signed the Bilbao Declaration requesting the annexation of East Timor by Indonesia. So, the UN declined Fretilin’s request (Durand 2011).

On December 7, 1975, 20 warships, 13 aircraft, and 20,000 Indonesian soldiers attacked the city of Dili.

The attack was strongly deplored by the UN General Assembly (Resolution 3485) (United Nations 1976), and the Security Council called for Indonesia to withdraw immediately, but no effective action was taken.

East Timor became Indonesia’s 27th province in the following year, by which time most of the population had fled into the mountains.

Indonesia, which had believed it could subdue the province within a few weeks, was forced to increase its presence to 40,000 troops. In August 1977, Indonesia attacked Fretilin’s headquarters in the mountains, interned civilians, and launched a military campaign of encirclement and annihilation (Budiardjo and Liong 1984; Taylor 1991). By the end of 1979, 80 percent of the resistance movement had been killed and 90 percent of its equipment had been destroyed.

In December 1978, the Indonesian military admitted to having interned 372,900 Timorese people (60 percent of the population) in 150 camps.

With very little land to cultivate, the prisoners experienced a famine the International Committee of the Red Cross said was as bad as Biafra and potentially as dramatic as Cambodia.

The situation did not improve in subsequent years.

Three other famines occurred, in 1981–1982, 1984, and 1987 (Defert 1992). The 25 years of Indonesian occupation involved considerable conflict and brutality. A detailed statistical report prepared for the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor cited a minimum of 102,800 conflict- related deaths in the period between 1974 and 1999.

Portuguese, Indonesian, and Catholic Church data have estimated 200,000 deaths, some 29 percent of the 1975 population (Government of Timor-Leste 2012; Silva and Ball 2006). Indonesian forces “strafed villages, burned crops, and pursued guerillas and their families into arid mountain areas” (Lamoureux 2004).

Many East Timorese women survived highly coercive, non-consensual relations with members of the Indonesian National Armed Forces, some of whom are the fathers of their children. These relationships are rarely spoken about in independent Timor-Leste. In some cases, a member of the security forces lived with a woman and her family on a permanent basis. In other cases, women were held permanently in military installations or summoned on a regular basis. Fear of stigma and discrimination has meant that this group of women remains marginalized in Timor-Leste society, unsupported, and often subject to ongoing violence (Peake et al. 2014).

Indonesia imposed a system of forced displacement and a complex system of public services, which included expansion of schools and health facilities (Fonseca and Almeida 2015). It employed thousands of Timorese public servants, conditional on membership in a pro-Jakarta political party (Gunn 2007). Indonesia also sought to replace Portuguese with Indonesian as the language of the media and public institutions. The Soeharto government passed legislation decreeing that all Indonesians, including those in Timor, must adhere to one of five official religions, which included Roman Catholicism. Many of those who had previously adhered to animism or atheism now chose to define themselves as Roman Catholics, whose share increased from 20 percent in 1975 to 95 percent by the mid-

1980s. In part, the East Timorese used this as a way of demonstrating their opposition to Indonesian rule (Roberts 2019).

Each year between 1976 and 1982, the UN demanded that Indonesia withdraw its troops from East Timor and allow the people to choose their own government. After 1982, the UN arranged for continuous talks between Indonesia and Portugal to try to find a solution to the problem. However, no major country supported East Timor. The United States felt that Fretilin was pro-Communist and was also concerned about ensuring America’s continued use of deep-water passages around Indonesia. Australia was more interested in trade with Indonesia, and Portugal did not want to jeopardize its chances of joining the European Common Market.

Please Look for Part III tomorrow

Nick Morris/ eyesoneast-timor